Learn

The War for Independence

As you learn about the major events of the Revolutionary War, keep this map open:

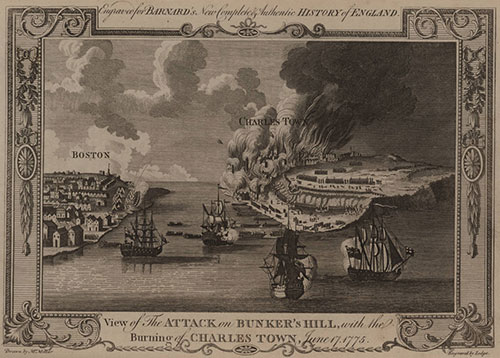

Battle of Bunker Hill

In June of 1775 as the Second Continental Congress met, British and colonial forces were building up around Boston. Approximately 20,000 poorly armed Patriots trapped the British in Boston while they gathered badly needed cannons and other supplies by capturing Fort Ticonderoga from the British in New York.

On June 17, 1775 in the Battle of Bunker Hill, British Redcoats led by Generals Gage and Howe launched a frontal attack on the colonial forces, which had taken higher ground upon Breed's Hill.

Following three devastating British attacks, the colonists were forced to retreat from the hill after using all of their ammunition.

The battle was a British victory; however, all was not lost for the American Patriots, who lost nearly 400 men, compared to over 1,000 British casualties.

Although the colonials lost the Battle of Bunker Hill, they gained morale and the respect of British soldiers who now viewed American Patriots as a formidable foe.

Patriot Determination

American Patriots were not broken by the loss at Bunker Hill. On the contrary, their spirit and determination to defeat the British was even stronger.

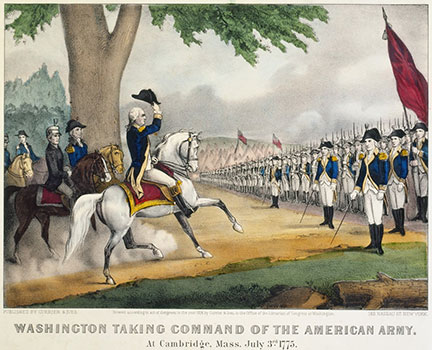

In July 1775, General George Washington arrived in Boston after being named commander of the army. He worked to create a Continental Army out of the militia groups; however, it would not be an easy task.

John Adams believed that 1/3 of the colonists were Patriots, 1/3 were neutral, and the remaining 1/3 were Loyalists, colonists who remained loyal to Great Britain. Even Benjamin Franklin's own son, William, was a Loyalist throughout the war.

In January 1776, General Henry Knox arrived in Boston with the cannons that were taken at Fort Ticonderoga. By March, the British realized they could no longer hold Boston. They moved their army, along with approximately 1,000 Loyalists, to Canada.

The next showdown was in New York in the summer of 1776. British and German troops battered Washington's poorly trained and equipped army. By October, the British had forced the Continental army to retreat.

Battle of Trenton

The fall of 1776 spelled disaster for Washington's Continental Army as they were forced out of New York. A victory was of vital importance because many of Washington's troop enlistments would be up with the New Year. He decided to go on the offensive and abandon the tradition of not fighting in the winter in order to get a badly needed victory.

General Washington and his army left their camp and spent Christmas night, 1776 crossing the icy Delaware River into New Jersey. Their attack surprised the Hessian forces encamped at Trenton, New Jersey.

The Battle of Trenton was a decisive victory for Washington and lifted the morale of the Patriots. A victory at Princeton followed shortly after the Battle of Trenton. General George Washington was becoming legendary.

Battle of Saratoga

The year 1777 was another tough one for the Americans. British Generals John Burgoyne and William Howe devised a plan to "divide and conquer" the colonies. Washington attacked General Howe at Brandywine Creek and at Germantown. Both ended in American defeats.

Meanwhile, General Burgoyne conquered Fort Ticonderoga and headed for Albany. However, his progress was slowed by his cumbersome entourage, which contained thirty carts of his personal belongings. Burgoyne was stopped and defeated at the Battle of Saratoga. This was a turning point in the war for the Americans because it boosted colonial morale, prevented New England from being cut off from the rest of the colonies, and encouraged the French to openly support the Americans' cause.

A World War Emerges

The French and Spanish governments had been supplying the Americans with guns and munitions through fake supply companies since the onset of the American Revolution. This was not simply an act of kindness. They too were British enemies and did not want their European rival's strength to be enhanced by the growth of the American colonies.

The American victory at Saratoga convinced France that the Patriots could indeed win the war with their help, especially the help of the French navy.

A year later, Spain joined the war as France's ally. Thus, Britain was now in a world war with fighting forces split between Europe and the Americas.

French Allies

Ben Franklin was sent to Paris to push for an alliance with France just a few months after independence was declared.

On February 6, 1778, an official treaty of alliance was signed with France. However, the French had been secretly aiding America against their longtime rivals with loans, supplies, and even volunteers.

Gilbert du Motier (best known as the Marquis de Lafayette) was a French volunteer before the alliance. Later he became a general in the American Continental Army. He was not even 20 years old when he began his service! He became good friends with Washington at Valley Forge and participated in battles at Brandywine, Monmouth, and Yorktown.

Valley Forge

While awaiting French aid, General Washington concentrated on spending the winter (1777-1778) at Valley Forge building his Continental Army into a professional fighting force – one that would not retreat at the first sign of a British bayonet.

Valley Forge was one of the toughest challenges Washington's army had to face. Their enemy was not the British redcoats; it was hunger, disease, and bitter cold weather.

Baron von Steuben, a volunteer from Prussia, trained and drilled the men in the deep snow at Valley Forge, molding them into a professional army.

Battle of Monmouth

Washington's army would soon test their newly learned new skills at Monmouth, New Jersey, in June 1778. The British retreated at the Battle of Monmouth, which was the last major battle in the North.

Loyalty Tested

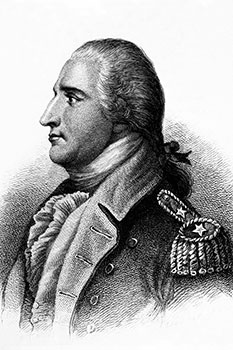

At the beginning of the Revolution, Benedict Arnold was one of the rising stars of the Continental Army. He injured his leg at the Battle of Saratoga, which his brilliant battlefield leadership helped to win. According to historian George Neumann, "Without Benedict Arnold in the first three years of the war, we would probably have lost the Revolution."

Bitter from wounds and being passed over for what he felt were deserved promotions, Benedict Arnold was made famous for his traitorous plan to sell West Point to the British.

Benedict Arnold's plan was discovered when they captured Major John Andre who was later hanged as a spy. Benedict Arnold managed to escape and was named a Brigadier General in the British Army.

War in the South

The British turned their attention to the South, where they envisioned thousands of Loyalists rising up to defend the British crown. Initial British victories at Charleston and Camden, South Carolina, caused great concern for General Washington, who was entrenched against the British in New York.

Washington sent General Nathanael Greene to replace General Horatio Gates as commander of the Southern forces after the defeat at Camden in August 1780.

American victories at the battles of Kings Mountain, Cowpens, and Guilford Courthouse regained Southern control and forced the British to retreat out of the Carolinas, relinquishing all they had gained.

Battle of Yorktown

After the Battle of Guilford Courthouse, General Cornwallis, the British commander of the Southern Campaign, left the Carolinas and headed for Virginia to meet Benedict Arnold who was now a British general . They began raiding the state of Virginia and met little resistance until June 1781.

Cornwallis retreated to the coastal town of Yorktown, where he could receive supplies and reinforcements by sea.

In the meantime, Washington's army was entrenched in New York. He requested French naval assistance and was told the French could assist for a couple of months, but not in the shallow New York Harbor.

Washington seized the moment and the French offer of naval aid, by heading South to Virginia in pursuit of Cornwallis' army at Yorktown. Cornwallis thought he would receive reinforcements by sea at Yorktown. However, the French navy had set up a blockade and was controlling the Chesapeake Bay, rather than the British.

See larger version of Battle of the Virginia Capes, 5 September 1781 by Vladimir Zveg, 1962.

George Washington's Continental Army had moved into Virginia to block off Cornwallis's escape route inland. Cornwallis was trapped. The bombardment started in September of 1781. Cornwallis had no escape route with the French naval blockade of Chesapeake Bay.

Together, Washington and the French were able to inflict the final blow on the British in Yorktown. On October 19, 1781, Cornwallis and his nearly 8,000 troops surrendered to General Washington.

Additional Resources

Explore the resources below to learn even more about the American Revolution: