Review of Congress at Work

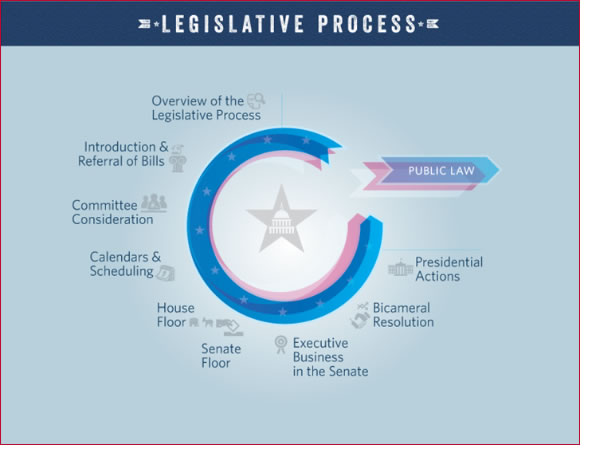

The primary job of Congress, the process of enacting legislation, is a long and complicated one. You have learned that much of the work of Congress is done by committees, which play a significant role in sorting through the many bills introduced in each session. We have also learned that political parties play a significant role in organizing and carrying out the work of Congress. Political parties elect the leaders in Congress who are charged with advancing the policies supported by their party in each house of Congress. Party leaders are regularly called on to speak to the press regarding issues before Congress. In addition to serving as spokespersons, party leadership organizes the work of Congress. Watch Overview of the Legislative Process (5:10) to learn more.

The United States Capitol.

How a Bill Becomes a Law

In this lesson you will learn how a bill proceeds through the House of Representatives and the Senate. After it passes committee, it goes to the full House or Senate for debate and a vote. A bill only becomes a law after a majority vote in both houses and it is signed by the President.

Introducing a Bill

Laws begin as formally introduced legislation or a draft of a law called a bill. The idea for a bill may come from a citizen like you, a political interest group, or even the President. After a bill is drafted or written, it must be introduced by a member of the House or Senate. Revenue bills have to originate in the House.

A representative in the House may sponsor a bill and officially introduce it by placing it in a wooden box on the clerk’s desk called the hopper. Bills are simply handed to a clerk in the Senate. The clerk assigns a legislative number, starting with H.R. for bills introduced in the House and S. for bills introduced in the Senate.

Watch Introduction and Referral of Bills (3:20) to learn more.

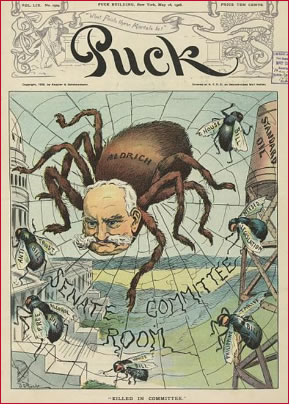

Committee Action

After a bill is introduced, it is assigned or referred to one or more committees with jurisdiction over the issues in the bill. The Speaker of the House assigns bills to standing committees while the majority leader assigns bills in the Senate.

Committees and/or subcommittees study a bill and hold public hearings in which they may hear expert testimony concerning the bill. Committees may take several actions:

- Markup or make revisions or amendments to the bill before voting to release it

- Report it out or release the bill with a recommendation to pass it

- Table the bill or lay it aside so it cannot be voted on, otherwise killing the bill.

The image is a political cartoon. This 1906 illustration shows Nelson W. Aldrich as a large spider on a cobweb labeled "Senate Committee Room" spread between the U.S. Capitol and a "Standard Oil" tower, on which several flies have landed.

Watch Committee Consideration (3:40) to learn more.

Calendars and Rules

After a bill is released, the written report is sent to the whole chamber and is placed on the calendar or the list of bills awaiting action on the floor of either House of Congress.

In the House, most bills go to the Rules Committee before they reach the floor of the full House. The committee may adopt rules that determine the procedures for how the bill will be considered by the House. Closed rules limit debate and forbid amendments to the bill. Open rules allow amendments to a bill while modified rules limit amendments on parts of a bill. The Rules Committee can be bypassed and debate limited to forty minutes under the suspension of the rules procedure which requires two-thirds of members to agree.

In the Senate, scheduling of legislation is done by the majority leader. A bill may be brought before the chamber by the majority leader making a motion to proceed and getting a majority vote by those present.

Watch Calendars and Scheduling (2:36) to learn more.

House Floor Action

After a bill goes to the Rules Committee, the Speaker of the House decides if and when it will reach the floor or the full House for debate.

The House essentially forms itself into one big committee called the Committee of the Whole to debate and amend a bill. Debate is guided by the sponsoring committee and time is divided equally between the parties. Any amendments must be germane or closely related to the subject or purpose of the bill. In other words, no riders should be attached to the bill while it is on the floor. A rider is a provision attached to a bill that is unpopular and unlikely to pass on its own. The measure is designed to cause a bill to “ride” and pass despite the unpopular measure or to kill a bill because of the unpopular attachment.

When debate is completed, the House votes on amendments and then the bill as a whole. There must be quorum or a majority of the members present (at least 218) to have a vote.

Watch House Floor (3:54) to learn more about debate in the House.

Senate Floor Action

Once a bill is placed on the Legislative Calendar by the majority leader and a motion to proceed is adopted, it goes to the Senate floor for consideration. The debate and amendment process in the Senate is not limited, so members can speak as long as they want - and may even filibuster unless cloture is invoked. Senators may also attach riders to a bill since amendments do not have to be germane. After a possibly lengthy debate process, the Senate will take a final vote on the bill. The final vote is taken by a roll-call (not electronically like the House) and requires a simple majority for approval of a bill.

Watch Senate Floor (4:18) to learn more about debate in the Senate.

The 111th United States Senate.

Conference Committee

After a bill passes one chamber of Congress, it is sent to the other chamber to go through a similar process. Both the House and the Senate must pass an identical bill before it is sent to the President. If the two chambers pass different bills, they are sent to a Conference Committee made up of members from each chamber to work out the differences.

The bill will die if the conference committee members do not reach an agreement. However, the committee usually reaches a compromise. Finally, conference report is written and submitted to each chamber for approval before the bill is sent to the President. Watch Resolving Differences (3:30) to learn more.

The United States Capitol.

Presidential Action

The final stages in the legislative process involve interaction between the legislative and executive branches of government. After Congress passes a bill, it is sent to the President for review. The President may:

1. Sign the bill making it a law.

2. Veto or refuse to sign the bill and send it back to Congress. A veto can be overridden by a 2/3 majority vote of Congress.

3. Pocket veto or choose not to sign the bill within 10 days (if Congress is in session the bill becomes a law, if Congress adjourns it does not).

This power to approve or reject legislation gives the President strong bargaining power with the legislative branch and can even be used to shape the content of bills as they pass through the Senate and House.

President Obama signs a bill into law (White House).

The Bill Becomes a Law

When a popular bill is signed by the President, a formal signing ceremony is often held. Legislators who worked for the bill's passage may be invited to see the bill signed. For public relations purposes, citizens who will be impacted by the bill are also included in many signing ceremonies. Traditionally, the President will use several pens to sign the legislation and give the pens to invited guests as a souvenir. Watch Presidential Actions (1:59) to learn more.

President Obama Signs Health Insurance legislation into law.

.jpg)

President Lyndon Johnson signs the Medicare Bill of 1965.

The Legislative Process

The image is a flow chart of the legislative process depicting the steps of how a bill becomes a law.