Objectives

Following successful completion of this lesson, students will be able to:

|

Overview

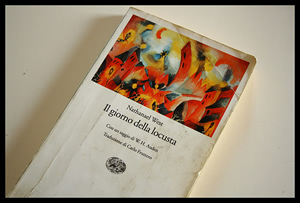

Can a fiction writer also write for film and television? Certainly. Authors like Robert Benchley and Nathanael West (who satirized Hollywood culture in "The Day of the Locust") can be found on the credits of a number of 1930s films, as well as even more famous names like Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Image courtesy of flickr user luiginter. This image is protected by a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

Writing for television and film differs from writing that is intended for the page. Screenwriters must write with a visual component in mind and are often forced to work within certain boundaries and budgets. Some argue that screenwriters of the past might have felt pressured to limit their imagination, but even in 1939, the film industry was capable of translating the novel of The Wizard of Oz to the big screen. Regardless, today's special effects are capable of realizing almost anything writers can imagine.

In order to successfully transition from the written page to the screen, a writer must learn the language of moving images, which includes acquiring a working knowledge of the technical language as well as learning to write in formats that can be followed by actors and a production crew.

In addition of learning to write for a visual medium, you should keep in mind how the different elements of multimedia can be used in television and film. You can find examples of text in movie titles, credits, and sometimes within the film itself. On television, you can see examples of text in the graphics of news stories, the slogans of advertisements, and statistics in a public service announcement. In both television and film, you can manipulate sound through dialogue, voiceover, music, and sound effects. You can even find still images embedded within moving images.

Check It Out

As early as 1889, Thomas Edison and his associates were experimenting with synchronizing sound to moving pictures. In 1926, Warner Brothers released Don Juan, the first commercial film to have accompanying recorded sound. Don Juan had a musical score but no dialogue. The next year, Warner Brothers released The Jazz Singer with music, sound effects and a few lines of dialogue. Sound had finally arrived in the movies.

Long before Star Wars, King Kong, or even Birth of a Nation, there was one of the most influential film illusionist of all time: a puckish French magician named Georges Méliès. One hundred years later, the whimsical "trick films" made by Monsieur Méliès include some of the most iconic images in movie history and continue to amaze and delight with their jaw-dropping creativity and vision. Méliès is now regarded as the Father of Special Effects.

A Trip to the Moon (French: Le Voyage dans la lune) is a 1902 French black and white silent science fiction film. It is loosely based on two popular novels of the time: From the Earth to the Moon by Jules Verne and The First Men in the Moon by H. G. Wells.

The film was written and directed by Georges Méliès, assisted by his brother Gaston. It was extremely popular at the time of its release and is the best-known of the hundreds of fantasy films made by Méliès. A Trip to the Moon is the first science fiction film and utilizes innovative animation and special effects, including the iconic shot of the rocketship landing in the moon's eye. It was named one of the 100 greatest films of the 20th century by The Village Voice, ranking in at #84.